- Year: 1971

- Released: 04 May 1977

- Country: Senegal, France

- Adwords: 2 wins & 1 nomination

- IMDb: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0067048/

- Rotten Tomatoes: https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/emitai

- Metacritics:

- Available in: 720p, 1080p,

- Language: Wolof, French

- MPA Rating: N/A

- Genre: Drama

- Runtime: 103 min

- Writer: Ousmane Sembene

- Director: Ousmane Sembene

- Cast: Andongo Diabon, Robert Fontaine, Michel Renaudeau

- Keywords:

| 7.1/10 |

| false% – Audience |

Emitai Storyline

As World War II is going on in Europe, a conflict arises between the French and the Diola-speaking tribe of Africa, prompting the village women to organize their men to sit beneath a tree to pray.

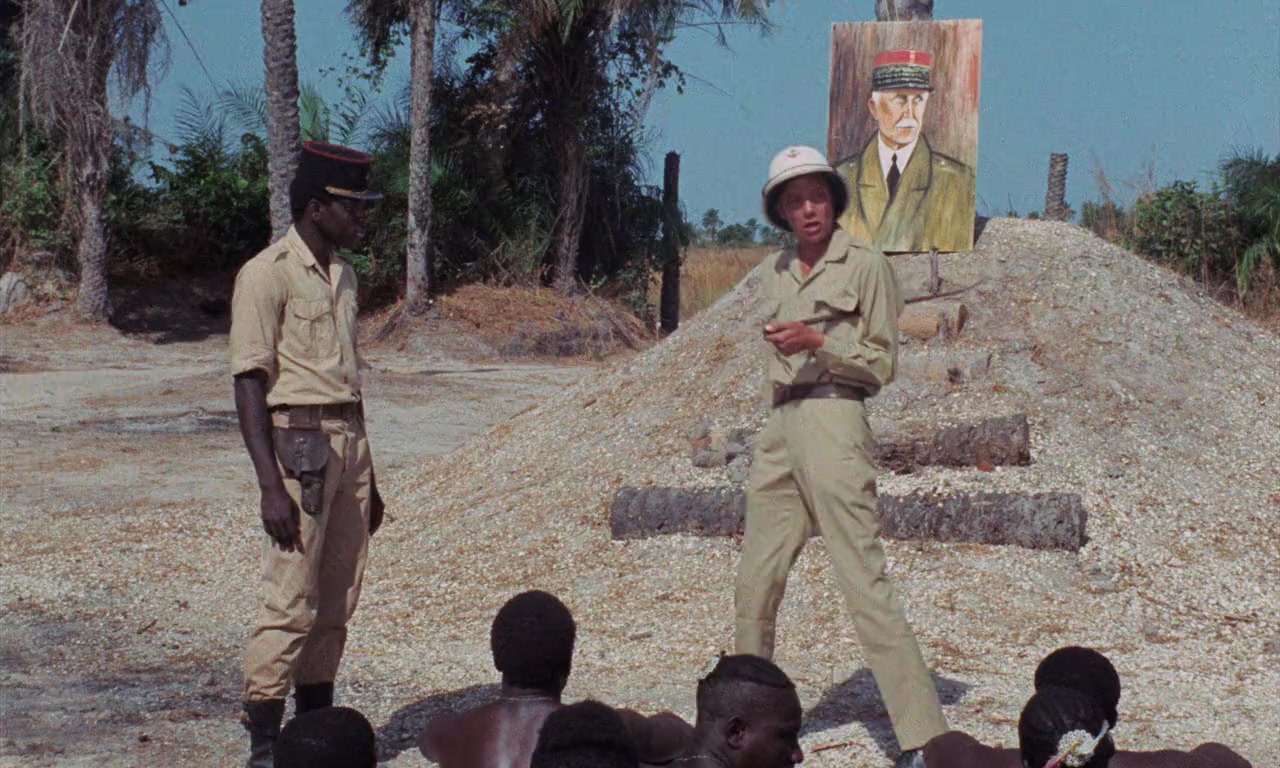

Emitai Photos

Emitai Torrents Download

| 720p | bluray | 928.93 MB | magnet:?xt=urn:btih:2B9D782E26E72A10CAC5B434D7189A9FB5C2D678 | |

| 1080p | bluray | 1.68 GB | magnet:?xt=urn:btih:F0ACD1F2F9AA0961A66052CEB3EFB7A044F97F9D |

Emitai Subtitles Download

Emitai Movie Reviews

“What must we do — live with this shame, or die?”

Here is a chilling portrait of how a heavily armed culture destroys an entirely outgunned traditional society.

In WWII-era Senegal, the spear-wielding, barefoot Diola people are being rubbed out of existence by French military thugs bearing firearms.

Draft-age men are being shipped out to Europe to fight the “white man’s war.” Women balancing baskets on their heads perform the back-breaking work of agriculture — “rice is a woman’s sweat” — but must yield their crop to the war machine.

Meanwhile, under a sacred tree where sacrifices are offered to the gods, village elders pass gourds full of palm wine as they wrestle with the impossibilities of their position. Where are ancient deities now that the French wield 20th-century firepower? The elders face an implacable truth — if they give up their sons and their food staple, their way of life will cease to exist.

One chief wants to challenge the French overlords — at least then, they will die as men. If only in their thoughts, others favor appeasement: “It’s better to be a living lamb than a dead lion.”

This drama plays out in a terrain of billowing ground dust and thatch-roofed huts whose slatted doors couldn’t bar one of the roosters that perpetually crows — much less a soldier barreling in with a bayonet. Overseeing it all, posted in the earthen square, are posters bearing the portrait of Marechal Petain.

The viewer comes to see that slavery, which thrived for centuries in this part of the world, never really went away. The chains disappeared, but the people remained desperately unfree.

Director Ousmane Bembene, whom I’d never heard of, creates an amazing, filmed-on-location portrait here of the evils of colonialism. We cringe to observe how the French, with few weapons, turn the unarmed into pawns. A teenager tries to flee conscription? Aucun problème! Hold his aged father at gunpoint, under a relentless sun, in the square. It’s just a matter of time before the boy submits to service, and an overseer snarls, “You think you’re smart? I’ll castrate you myself!”

The Diola do what they can to sustain their spirits. A drumbeat communicates that chief Djemcho has died on the fighting plain. (“Why didn’t you believe in our gods?”) Womenfolk, forced to sit in the sun until their give up their rice, want to fight back, but know resistance is futile. It’s only when a child falls to gunfire that they rise up to bury him according to tradition. If they must die in order to perform this sacred rite, then so it must be.

Apparently cast almost entirely by non-actors, this is an amazing work of art from Bembene, who believed that film should be a “school of history,” and “we shouldn’t be afraid of our faults and our errors,” according to Alicia Malone, who announced the movie on TCM. “Films could help people to question and challenge the world around them.”

“Emitai” has certainly left me questioning the legacy of colonialism. What a horrific blight on humanity!

Concept = 9; Production = 4

This frustrating film is brilliant in concept but intensely awkward in execution. His main themes throughout his career are hammered relentlessly: that male elders invited their oppression and that the society rests on the labor of women. But the philosophical issues are alluded to in passing and the use of non-actors portraying elders should have given far less time to their deliberations. The ending is far too abrupt and thwarts the understanding he was building up to all along. Compare this to his most recent film “Faat Kine” and you will see Sembene’s development as a storyteller.

Meanwhile, in Senegal

Gorgeous scenery, beautiful people, and an important, shameful history lesson. During WWII, Senegalese villagers were put in an impossible situation by France – forced to ship their sons off to fight in the war (as they had been in WWI), then later forced to turn over their precious rice crop to the war effort. They were told they’d be imprisoned and their village would be burned to the ground if they didn’t comply, and without the military strength of those controlling them, none of their options is good.

The film shows us at least some of the life and customs of the Senegalese, which includes turning to gods who seem absent and performing a couple of live animal sacrifices (beware, not all of this is hidden). More importantly, it shows their dignity and humanity, particularly in the looks on their faces in the tight shots director Ousmane Sembène regularly gives us, and which were my favorite part of the movie. This is contrasted by the inhumanity of the French, who force people to sit out in the sun as punishment, as well as block a funeral service. It’s pretty clear that they don’t see the Senegalese as human beings, at least in the complete sense of the word, and while watching it I wondered how these events would have been remembered by history had the black/white roles been reversed (and also how I myself might process it differently).

It’s tough to watch other Africans carry out the enforcement of French policies, and of course tough to fathom the cruelty in this example of colonialism. It was a deeply personal story to Sembène, who himself was drafted and fought in the war. The bitter irony of fighting for freedom as part of the “good guys” when his own people suffered atrocities and humiliation was not lost on him, and it’s a reminder that even nations with high ideals like “liberté, égalité, fraternité” often fall well short of them.